As a serious sewer, there are things you need to know about the fabrics you use, so that you can achieve the look you want. One of these things is knowing the weave of your fabric. Think all you need to know is how the fabric looks in your hand when you buy it? Not even close. Fabric weave (let alone content) determines durability, fit and even how it sews up. You have already proven this to yourself every time you buy jeans. You try them on in the store, and they fit great, but as you wear them, they losen up. See? You already know that twill will “grow”. Take a look at your jeans. See how the the weave looks diagonal? That’s a twill. It’s strong, but not terribly stable. With all of todays fashionable washes, you can probably see it better on the inside. Take a look.

Let’s start at the beginning. Fabric is made from warp and woof (or weft). The warp runs the whole length of the fabric, and the weft/woof runs across the short way from selvage to selvage. The selvage is where the weft yarns wrap around the last warp yarn to head back the other way. Along with the fiber content, the way the warp and weft cross determines the qualities of the fabric.

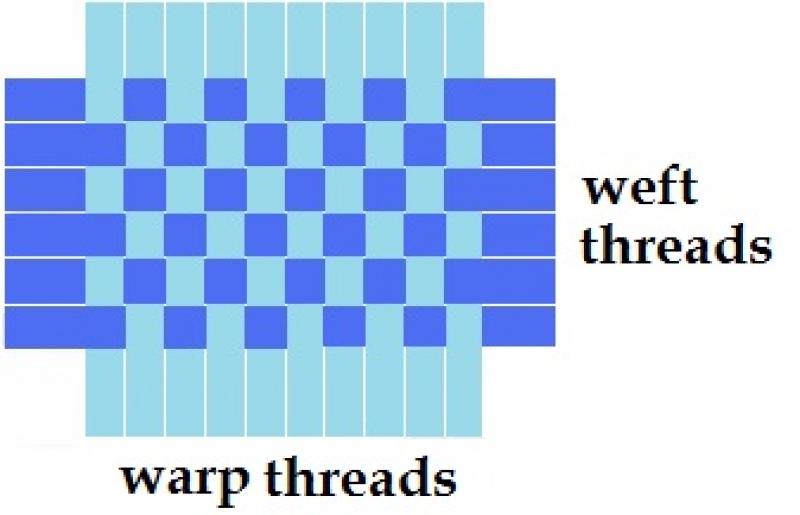

Tabby illustration from fabulous The Textile Research Center. http://trc-leiden.nl/trc-needles/index.php/component/k2/weaving/tabby-weave

The simplest weave is the tabby, or plain weave. Yes, this is where tabby cats get their name. They are “plain” cats. The tabby weave is the simplest one-one weave. This means that it’s just like those pot holders you made as a kid. It’s a simple over under pattern. It can be very durable, and is not going to “grow” with wear, like your jeans. You will find tabby weaves in calico, organza and batiste.

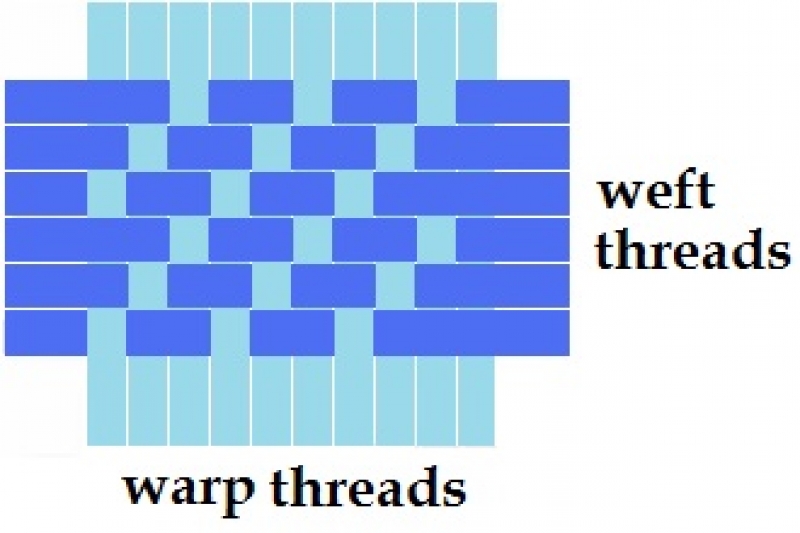

The Textile Research Center’s twill diagram

http://trc-leiden.nl/trc-needles/index.php/component/k2/weaving/twill-weave

Your jeans are made from twill. In a twill, the warp yarns float over two or more weft yarns. There are lots of variations on a twill that involve how steep an angle the diagonal takes, whether it’s right hand or left, and it also includes the herringbone. The twills have a softer drape than a tabby, are soft and strong, but can grow with wear. This can indeed be a good thing, as that’s how jeans get their custom fit. They grow where each person needs it, where the stress is put upon it. Twill is used in denim, gabardine, and tweed.

If we float even more threads, we have a satin weave. Satin is a weave. You can make it in any fiber you wish. Silk, is a favorite. Satins have long floats (long jumps between times the warp and weft cross) only on the face of the fabric. Though the fiber has the greatest impact on the effect, the long floats make the fabric shiny, and smooth. This also implies, no matter what the fiber, that it is prone to snags—something you need to think about for future wear. Satin’s close cousin, sateen, it pretty much the same theing except that its long floats are ceated with the weft, not the warp. It is usually made in cotton, and has a subtle sheen. Satin is usually made with silk, acetate, and polyester.

Wikipedia’s satin weave illustration. Wikipedia is also a great source for textile information. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Satin

There is so much more to weaves, and even more on fiber, and staple shape, and length to know. It fills books, and it’s a good thing to read, as knowing these sorts of things will help you pick the correct fabric for you project. You will avoid the disappointment that comes from spending hours building something only to find it does not behave as expected.

For more info: My college textbook: Essentials of Textiles by Marjory Joseph. You may also like the book Textiles in Perspective by my college professors, Betty Smith and Ira Block. You can get them for a few pennies on Half.com. Far less than I paid for them back in the day.